When senior Ruth Frezghi is asked what her experience at her church is like, she has difficulty explaining it. How could she explain what a Sunday morning at her Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church is like? The only true way that someone could understand what 8 a.m. looks like for her would be to go and pray with her, hum along with the songs in Amharic and even welcome the ice-cold holy water that the priest throws in each individual’s face at the end of service. Anyone who wants to understand even the surface of what senior Ruth Frezghi’s religion and experience is like might choose to see it first hand.

“They’d think I was weird probably (if they came to my church),” Frezghi said. “It’s so different than American Christian churches.”

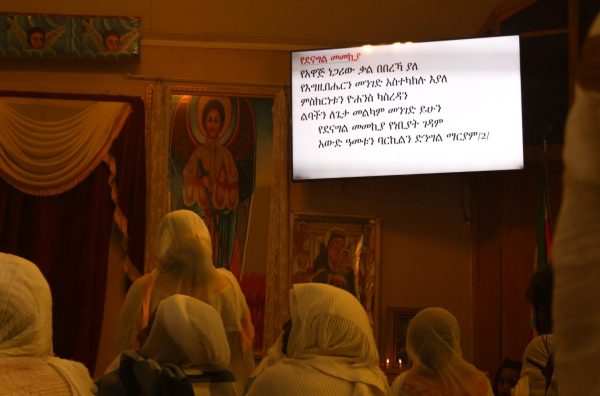

On Sundays, Frezghi dresses in white and covers her hair with a veil, like every other woman at her church. When she arrives to worship, she takes off her shoes, prays and finds her seat on the right side of the church. For the next three hours, Frezghi participates in communion, listens to the church choirs and shares a meal of traditional Ethiopian food with the other members of the church and girls her age.

While Frezghi spends every Sunday morning at her church in Omaha, she walks in her religion every day. It requires its followers to do certain things that other denominations of Christianity don’t. This is largely because her faith follows the Old Testament in addition to the New one.

“I pray, like, three times a day,” Frezghi said. “I pray before I eat. When I’m fasting, I can’t eat at all or drink any water, so that’s, like, very difficult, especially during that three day period where I’m just like hangry.”

Her faith has always been something her life has revolved around, with her mother, Aster Haile , being the one who has been building its foundation.

“I don’t believe that I am teaching (my children) religion as much as I am teaching them about faith in God,” Haile said. “I believe that’s important because it teaches them who they are and gives them purpose.”

Haile was born in Ethiopia and has lived in Sudan, Libya and Malta, and an island off of Italy, in addition to the United States. Frezghi was born in Malta before moving to America with her mother when she was a toddler.

Members of Frezghi’s church participate in worship during a Sunday morning service. A television displays lyrics in Amharic. “One challenge living in a predominantly white neighborhood is the loss of language,” Haile said. “Some things get lost in translation because my kids don’t speak as much Amharic because they are not immersed.” (Mary Jane Kushiner)

As adolescents often feel the need to fit or blend in with their peers, the individuality that following a religion like Frezghi’s can bring can be uncomfortable. Haile said it important to her that her children don’t feel this way.

“I want them to be independent, comfortable with who they are and have a healthy fear of God,” Haile said. “I want my kids to remember that whenever they pray, God is there and that their faith is uncompromising.”

While Frezghi hasn’t struggled “fitting in” or finding her place at GHS, since she’s found friends through her involvement in concert choir as well as other areas, other students who experience this barrier may find it difficult to.

“I feel like it can feel very isolating (practicing a different religion),” GHS counselor Melissa Ryan said. “Because people just don’t understand initially, that person may have to explain themselves or explain what they’re doing or why they dress. And that can be very vulnerable for a person and can open them up to criticism if somebody is not accepting of who they are.”

A large portion of the student body at GHS follows some form of Christianity, most commonly non-denominational, Protestantism or Catholicism. However, Frezghi is the only known student who is a member of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church.

While her religion sets her apart from her peers, it isn’t the only factor. Besides this being her ninth school since childhood, she’s also part of a minority in a school that doesn’t have the same diversity that other places in the state do.

“There’s about three Black people in this school,” Frezghi said, sarcastically. “I don’t think about it often, because I don’t, I don’t care. But I do think it does impact my life differently than, I guess, white students at GHS.”

Out of 991 students at GHS, there are 119 students who check anything other than white when registering for enrollment. Frezghi is part of this 12%. Some students and staff have questioned in the past whether this lack of diversity is a hindrance to school culture.

“There is definitely a lot to be gained from learning from people around you,” Ryan said. “Listening to their stories, listening to their traditions, their life history. That is how we develop empathy. And that can help us to navigate the world around us.”

Frezghi’s experience doesn’t look like anyone else within her grade, school or even district besides her sister. In addition to social barriers, she deals with hindrances to doing basic things like eating lunch with friends, too.

“Even school lunches, there’s a lot of food that I can’t or can’t do,” Frezghi said. On Wednesdays and Fridays, in addition to several holidays, Frezghi can’t consume any animal products. “So I guess, in that way, it affects me, but otherwise I don’t really feel like it matters.”

While religion isn’t something a person can see, Frezghi’s skin color is, and she feels like it has an impact on her life in and out of school. She’s said she has experienced physical, but mostly verbal bullying from her peers, specifically in the elementary schools that she attended outside of the Gretna district.

“I experienced people being racist to me, like, all throughout middle, elementary school,” Frezghi said. “It was really mostly elementary school, physical bullying, a lot of verbal. Being called a whore, that was crazy.”

Frezghi’s mom also feels the challenges that following a religion that no one else in the area follows, as well as speaking a different primary language, Amharic, creates.

“One challenge living in a predominantly white neighborhood is the loss of language,” Haile said. “Some things get lost in translation because my kids don’t speak much Amharic because they are not immersed.”

Bethel Kifle • Oct 14, 2025 at 3:37 pm

Beautiful story. I’m Ethiopian Orthodox as well and I relate very much.